Prior to the cataclysmic events of the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century, different individuals and religious movements at various points called into question and sought to challenge the authority and teachings of the Catholic Church in Rome. In fourteenth-century England, John Wycliffe (d. 1384) was one such individual. Indeed, some consider Wycliffe, and the religious movement he inspired, to be a precursor—or “Morning Star”—of the Reformation.

Probably born sometime in the 1320s in Yorkshire, Wycliffe lived for most of his life in Oxford, where he was a student and later taught theology. He was also a Catholic priest. Over time, however, Wycliffe became increasingly disillusioned with the Church of his day.

Wycliffe’s beliefs, which he advanced in his various political and theological writings, were radical for the times in which he lived. He maintained that the teachings of popes and clerics were self-serving, and designed only to help them amass further wealth and power. Wycliffe believed that churchmen should not exercise any worldly authority. He would surely, therefore, have disapproved of the career of his contemporary, William of Wykeham.

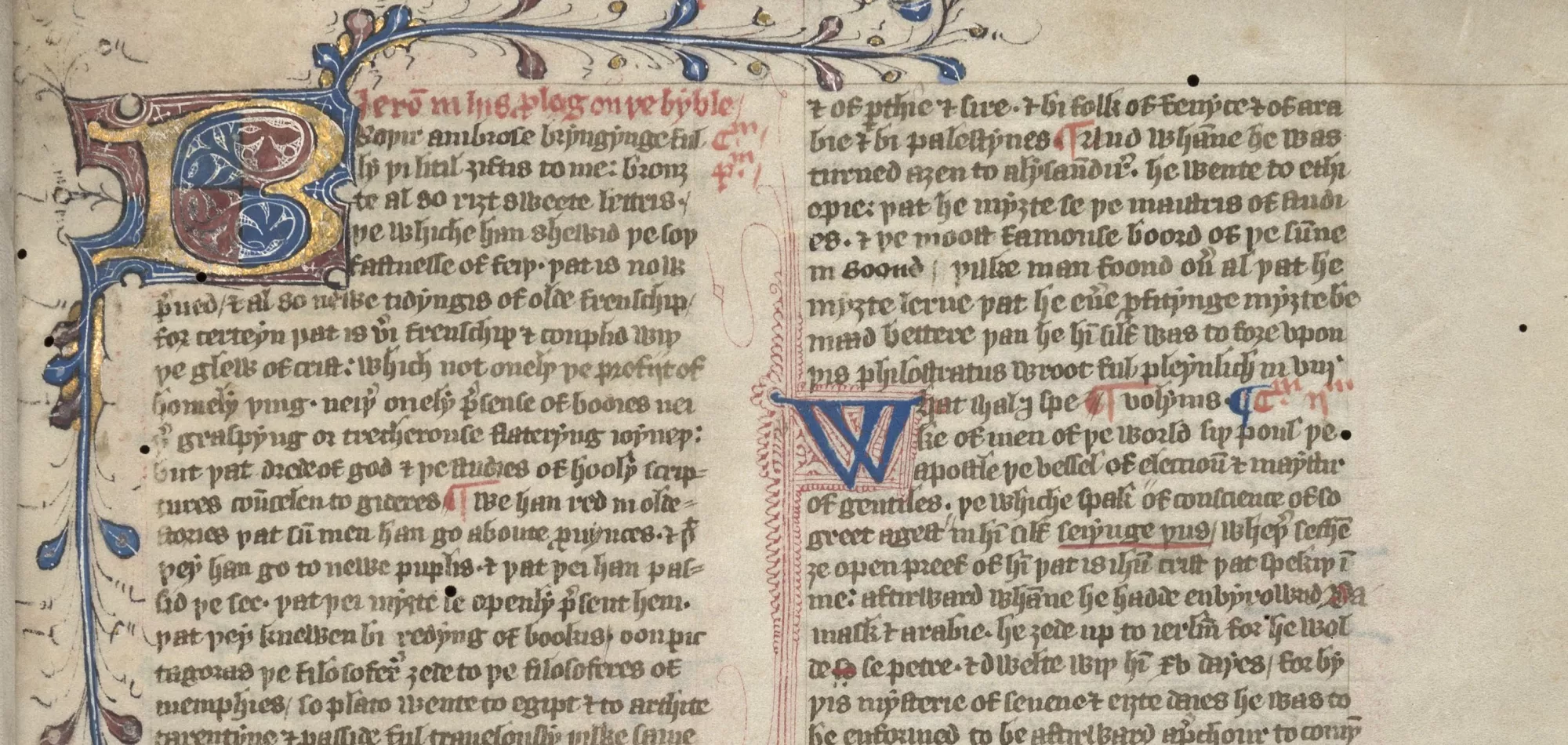

Wycliffe argued that the Bible was the only reliable authority regarding the Word of God and that all Christians should be able to read it in their own language. In 1382, he and his followers published the first complete translation of the Vulgate Latin Bible into English.

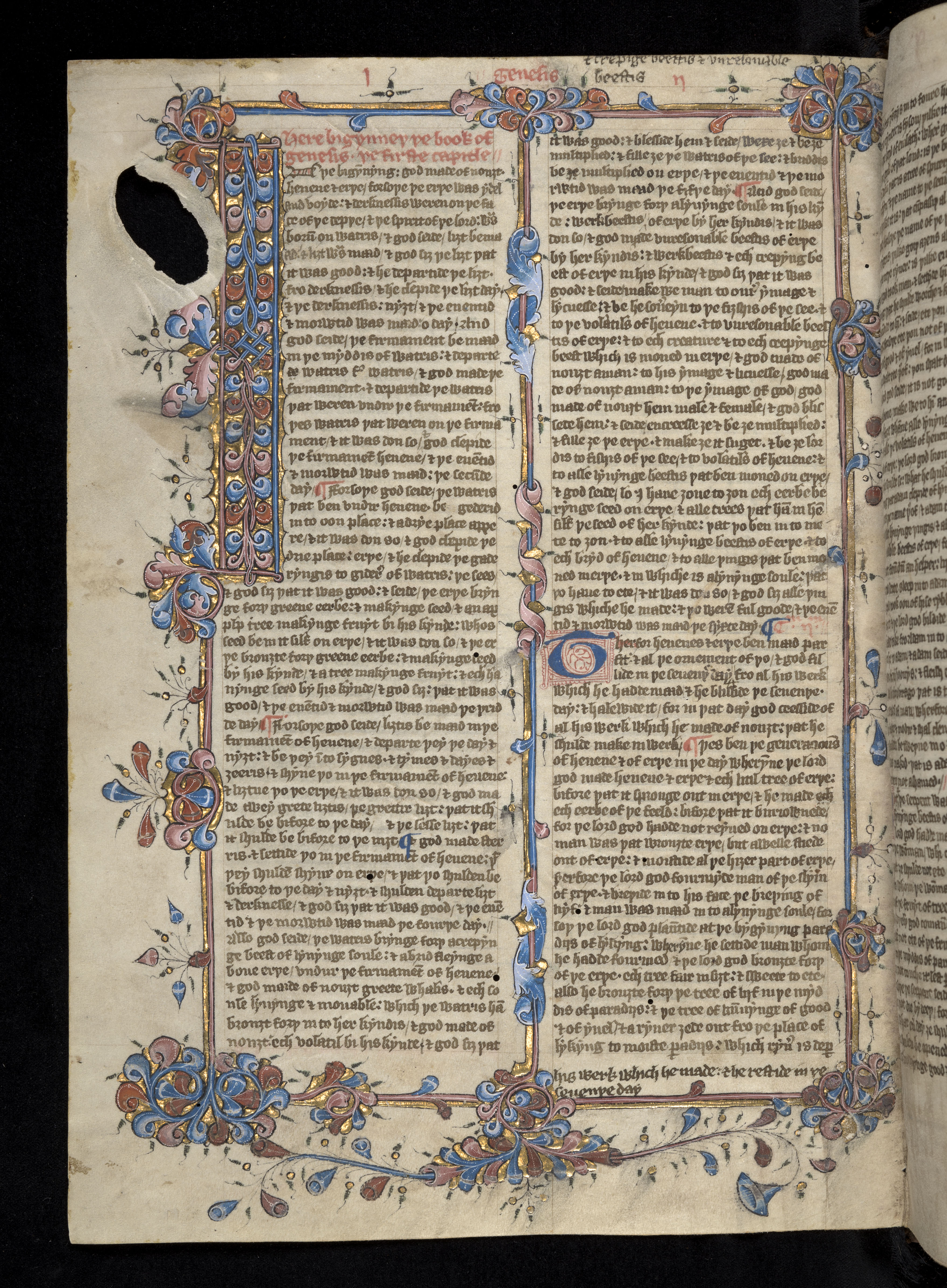

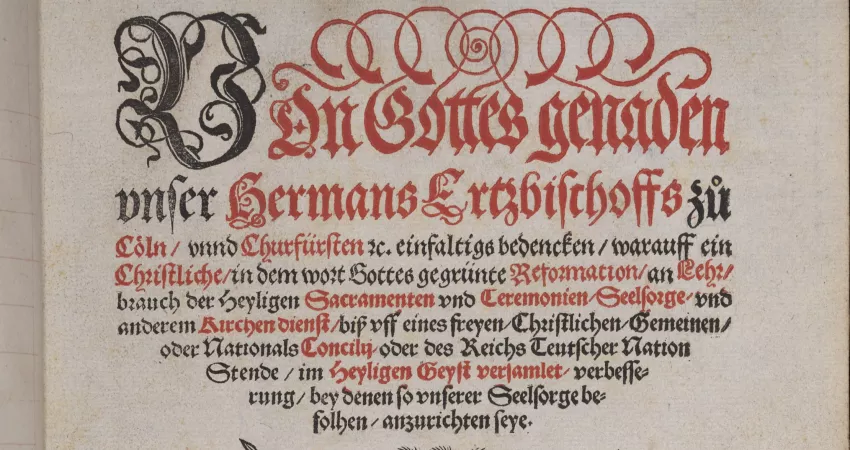

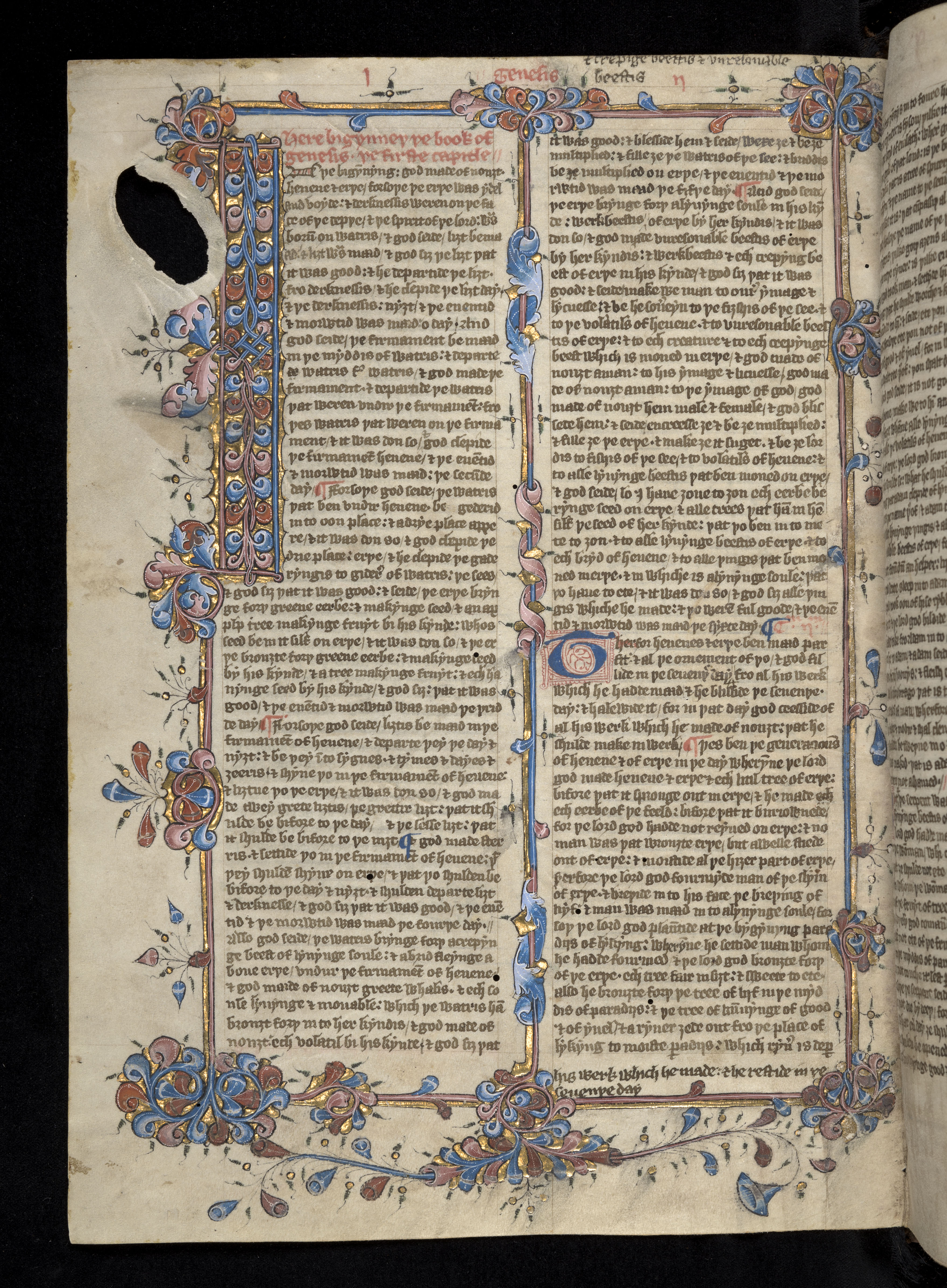

New College, Oxford, MS 66 is one such Wycliffite Bible (see image). It contains all of the books of the Old Testament, from Genesis to the Psalms, in the later English translation prepared by Wycliffe’s followers, known as Lollards. Wycliffe’s teachings were condemned by the Church, but they nevertheless spread widely throughout England and into Europe where they continued to attract supporters well after his death on 31 December 1384. Though it was officially banned, the Wycliffite Bible became the most widely disseminated text in English in the medieval period.

The style of decoration and script used in MS 66 indicate that it was produced sometime between 1415—when Wycliffe’s teachings were formerly declared heretical at the Council of Constance—and 1425. Each of the books of the Old Testament opens with a beautiful initial like the one displayed here. The text, however, is full of mistakes. On the page pictured here (f. 6v) alone, the scribe missed out two sections of text which had to be corrected by other scribes.

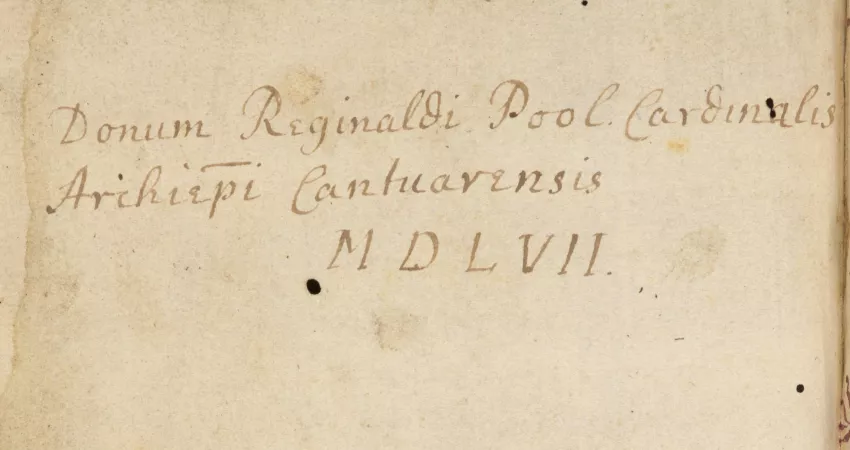

MS 66 is one of four Wycliffite manuscripts housed at New College. The other manuscripts are: a copy of the English translation of the New Testament (MS 67) which was donated to the college in 1558, an English translation of the Psalms (MS 320) which was bequeathed by New College alumnus Thomas Philpot (d. 1671), and a collection of Wycliffite sermons (MS 95). The entry of these manuscripts into New College’s collections reflects the changing religious attitudes of its membership during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and beyond (see more about this below).