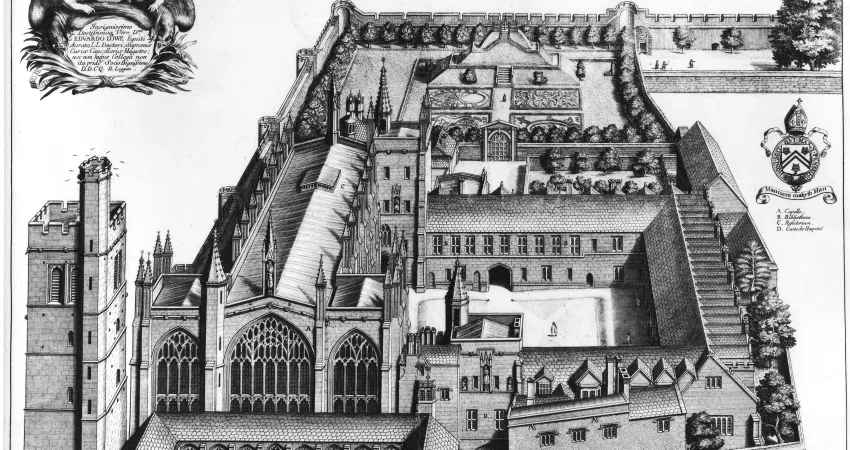

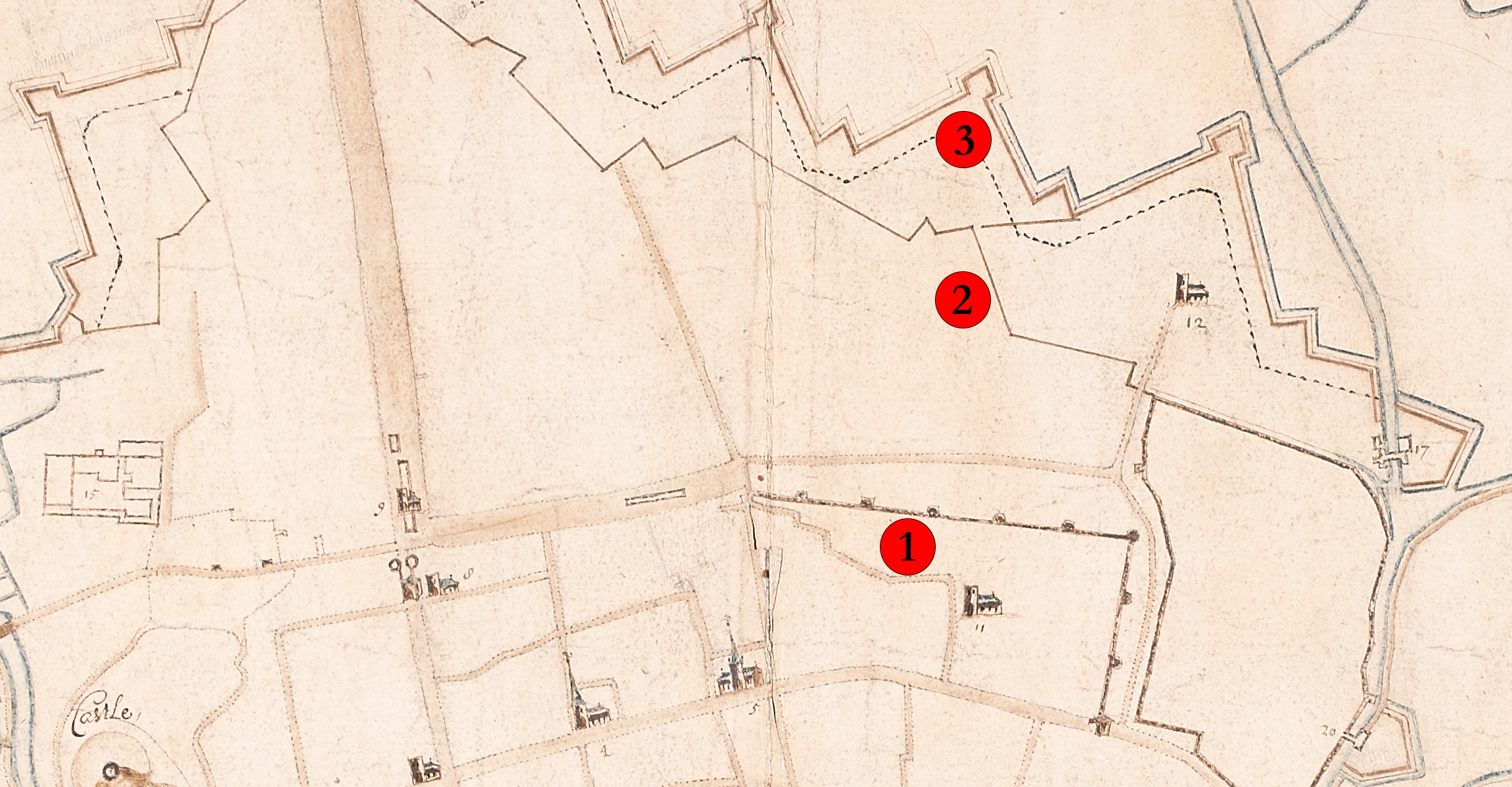

The pamphlets above showcase the politics of the English Civil War and the propaganda efforts of both sides, but New College was also very much physically affected by the outbreak of hostilities. Oxford, located in the heart of the Thames Valley, saw some of the most bitter fighting of the conflict as it occupied a strategic position between Parliamentarian London and the Royalist west of the country.

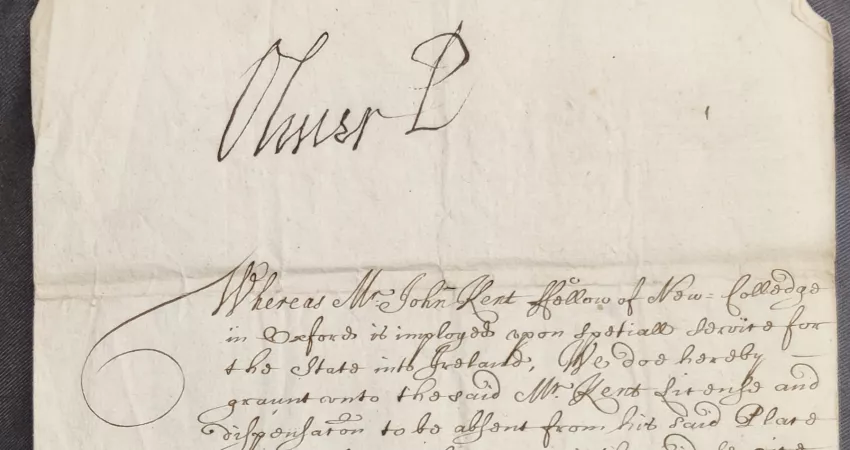

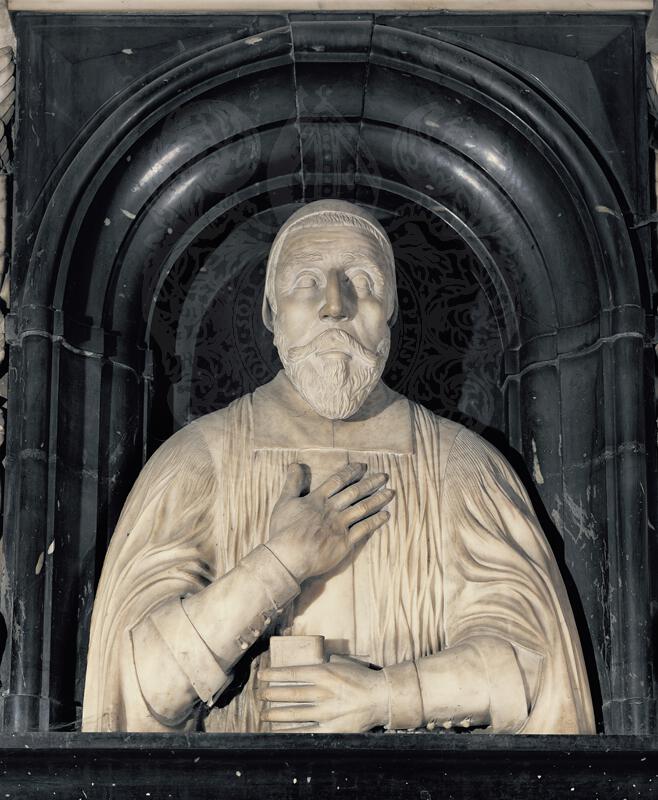

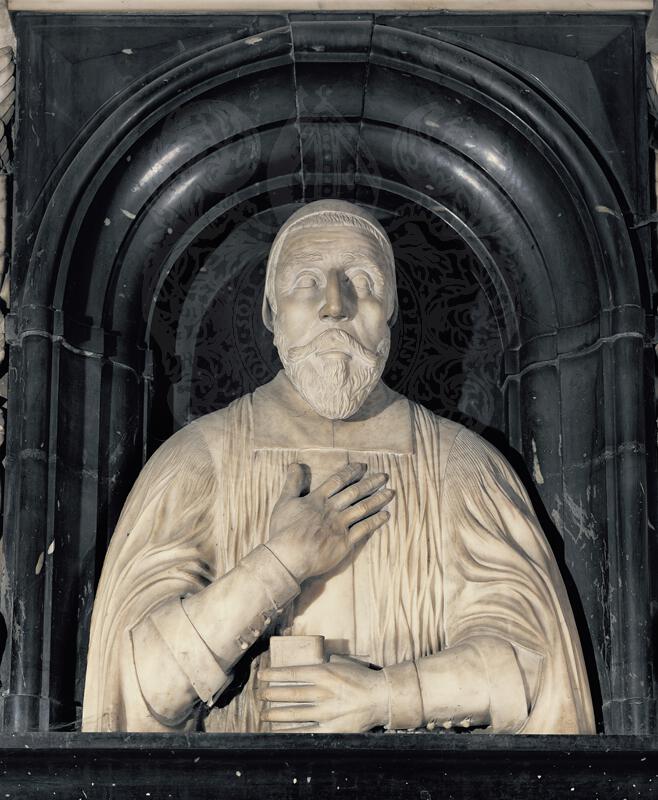

Indeed, conflict reached the city straight away. In September 1642—just one month after the outbreak of hostilities—it fell to New College’s Warden, Robert Pincke (1573–1647), pictured here, to organise the defence of the entire university after the vice-chancellor, the Bishop of Worcester, had abandoned Oxford. New College’s tranquil front quad was transformed from a site of academia to a warzone—with soldiers practising their drills on the hallowed grass.

These efforts were far from successful. Parliamentarian Lord Saye and Sele (1582–1662) ransacked the Warden’s study during this chaotic period and arrested him en route to the battle of Edgehill. Saye and Sele was in fact a New College alumnus and even related to William of Wykeham, so his actions truly highlight the divisions caused by this conflict not only at a national level, but even amongst the membership of the college itself.

After the inconclusive battle of Edgehill, Oxford essentially became the King’s administrative and military capital for the rest of the conflict. Convocation House in the centre of the city housed King Charles I’s parliament whilst the King was resident in Oxford during the war. The city, and New College itself, therefore understandably became a military target for the first time in its history.

New College reacted to this threat by preparing to defend itself more effectively against attack. The item pictured below encapsulates these preparations. Now held in New College’s chattels, it is one of the remaining sets of armour ordered for the Fellows by Robert Pincke. Note how the words ‘New Col’ have been engraved into the breast plate to mark the college’s ownership.

The purchase of suits of armour was by no means the only change experienced by the college during this time. In fact, the entire college was transformed. New College contributed to the King’s war effort by converting the cloisters and Bell Tower into a major royalist arsenal. The cloisters quadrangle was apt for this purpose, as it was a natural fortress, protected from the weather and from unauthorised entry. To enable easier loading and unloading of ammunition, a hole was knocked through the west wall of the cloisters—as this could be easily guarded, the New College ammunition store was deemed to be more secure than the castle itself.

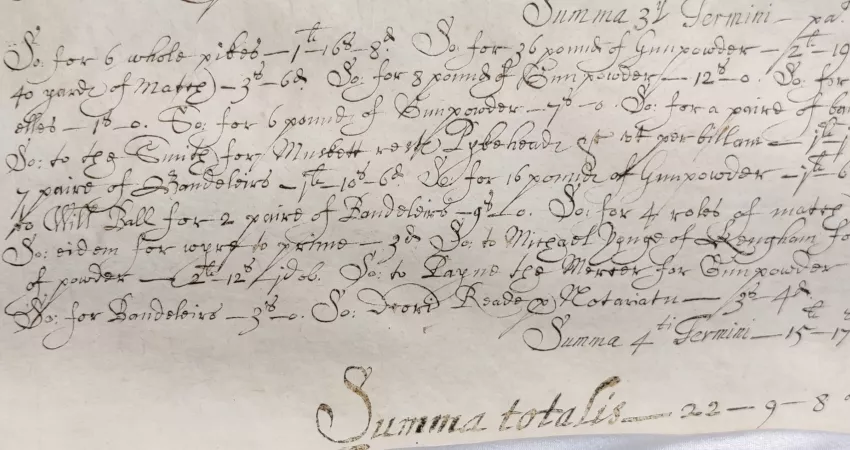

A fascinating document in our Archives records this period in New College’s history. Below, you can see an entry in the Bursar’s Account Roll for 1641/2 (NCA 7665). Essentially a list of all college expenditure, there is a total expenditure of 22 pounds, 9 shillings and 8 pence on a wide range of items used for military purposes—a not inconsiderable amount of money at this time. Click on the dots to discover more.

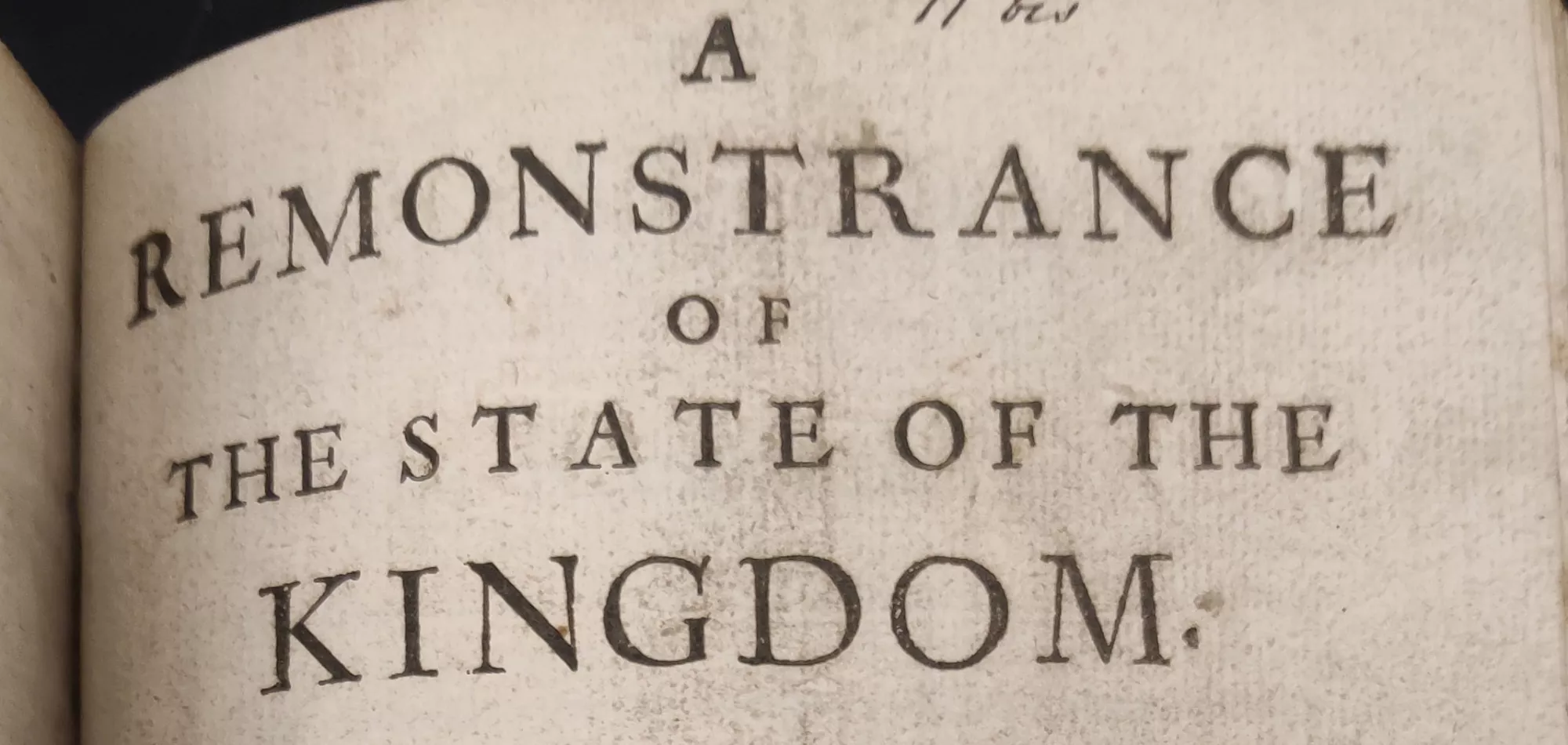

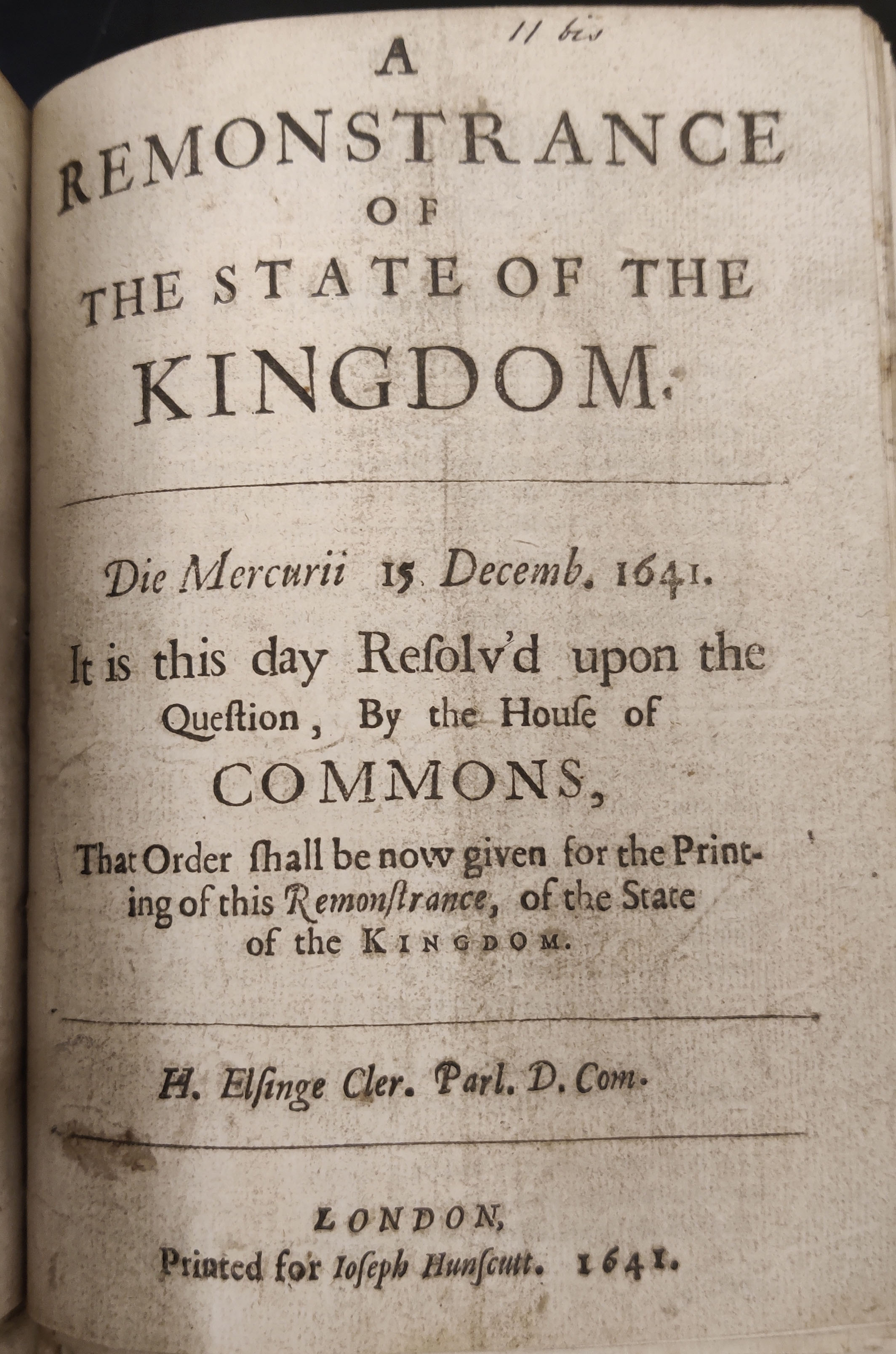

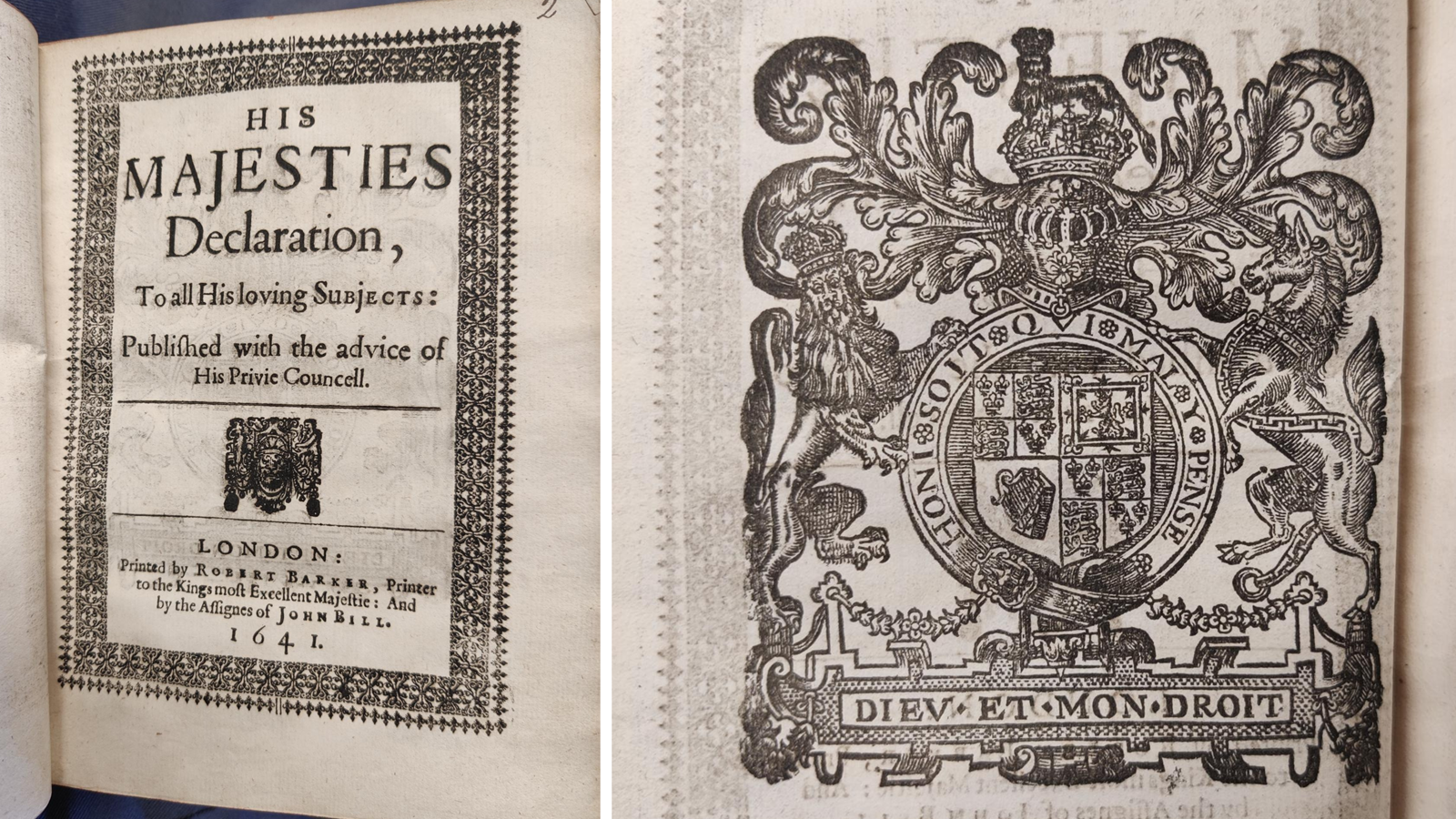

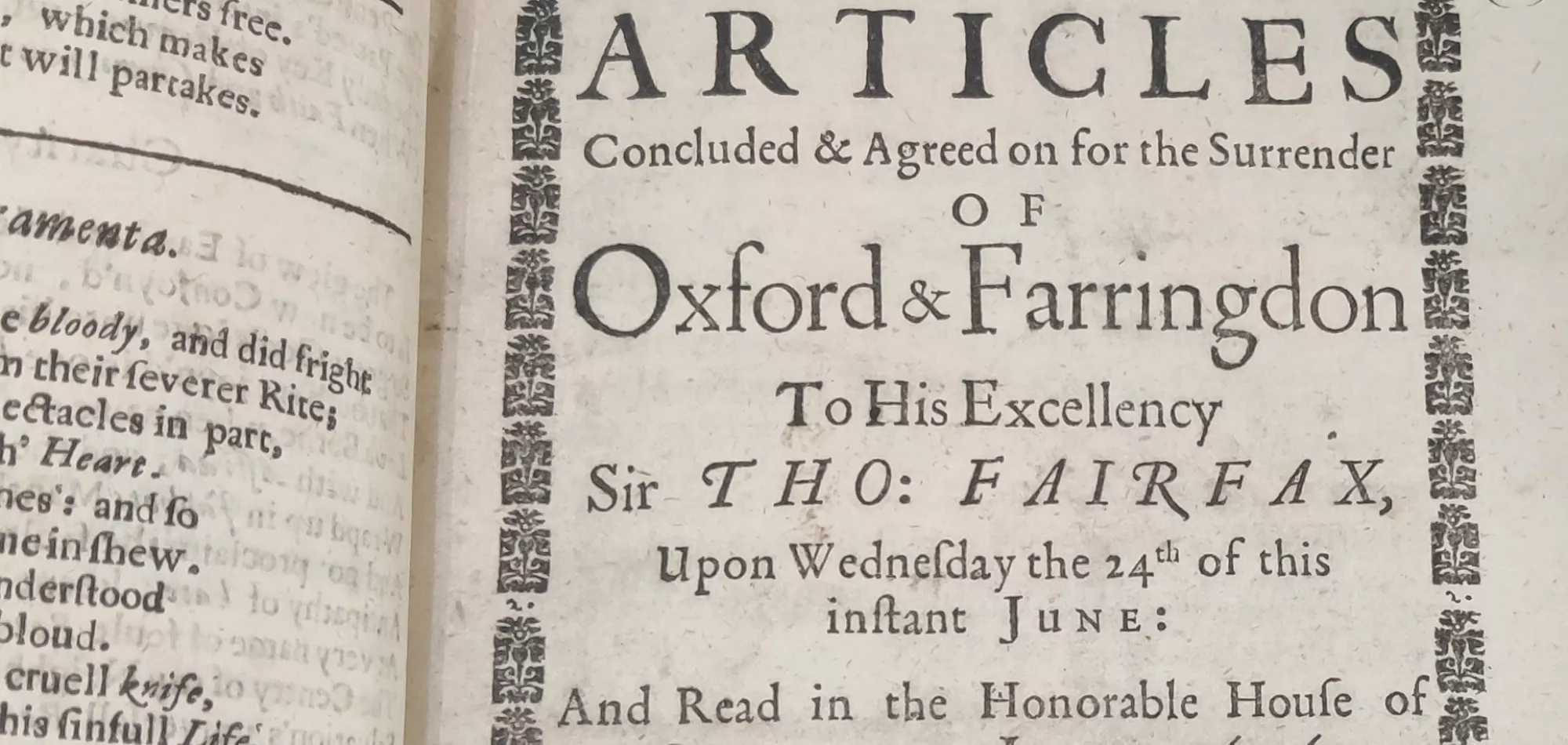

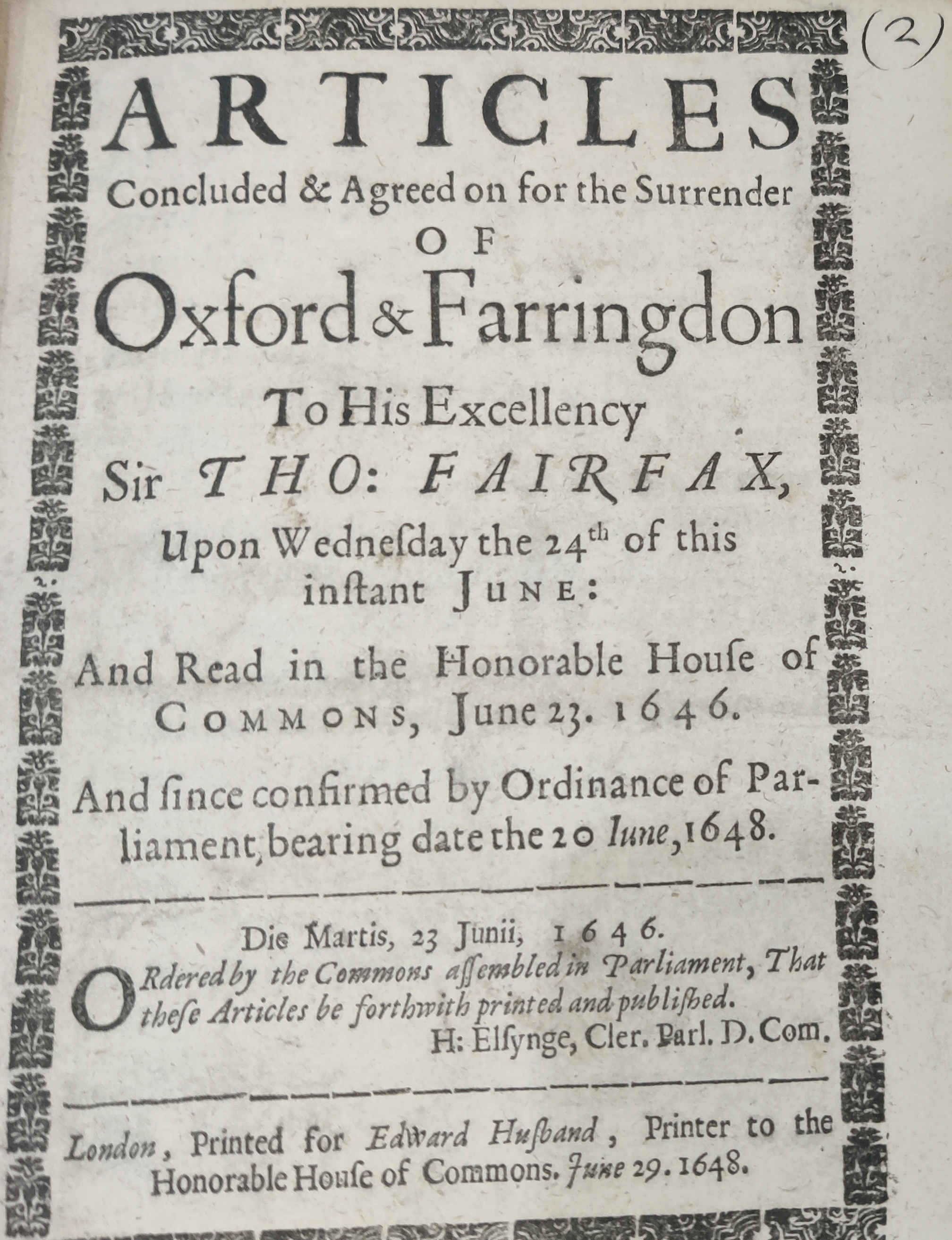

To avoid this fate, the city decided to surrender in June 1646—a momentous event commemorated in the collections of New College Library. Here, you can see the title-page of a

To avoid this fate, the city decided to surrender in June 1646—a momentous event commemorated in the collections of New College Library. Here, you can see the title-page of a